After 10 years, it’s happening.

Annual memberships in Portland’s city-owned, Nike-sponsored public bike sharing system went on sale at 6:20 a.m. Tuesday, and the 1,000-bike system to be known as Biketown will get one of North America’s largest-ever bike share launches on Tuesday, July 19.

Memberships will cost $12 a month with a one-year contract that comes with 90 free minutes per day. If you don’t want to make an annual commitment, you can opt to buy a single ride of up to 30 minutes for $2.50, or a 24-hour pass with 180 free minutes for $12.

In all cases, you’ll pay 10 cents per minute for any additional time over your free allotment.

Unlike with most other U.S. bike sharing systems, there won’t be a month-to-month option for most users.

System will be unusual in several ways

(Photo: City of Orlando)

As we’ve discussed in our previous reporting, Portland’s “smart bike” system will be one of the country’s first.

If you want to drop a Biketown bike anywhere on the same block face as one of the official racks, that’ll count as being “docked” because the bike will be able to detect that it’s close to home base. This eliminates one of the major frustrations of most bike share systems: arriving at a station to find it full.

If you want, you’ll also be able to drop one of the smart bikes away from a station, anywhere in the service area, for a $2 penalty fee. If you pick up a bike that’s away from a rack and finish your trip inside a “station” area, you’ll get a $1 credit to your account.

Biketown will be the largest such system in the United States so far, though smaller smart bike systems are operating in Phoenix, Tampa, Boise, Orlando and elsewhere.

The first 500 people to register for annual memberships will get the first month free.

Some employers and apartment buildings may choose to offer discounted memberships for their employees. Those will go on sale later in the summer.

Final station locations invest heavily in west side

The first 100 stations in the Biketown system — city officials hope to gradually add more over the coming years — will be concentrated mostly in downtown and inner northwest Portland, which the city says have the best combination of residential density, commercial density, job density, transit service and low-income residents.

“Every station has multiple points of demand that we can pull off of,” city bike-share manager Steve Hoyt-McBeth said in a press briefing Monday.

On the west side, if you’re between NW Vaughn, NW 25th, SW Vista and the lower part of the Interstate 405 loop, you’ll rarely be more than three blocks from a station.

“We really took lessons from cities across the country that bike share works best not only when you put stations in high-demand areas, but when you put a high level of service in those areas,” Hoyt-McBeth said.

Six stations will sit immediately off the Transit Mall; four will sit immediately off the Park Blocks.

In addition, a decent swath of the inner east side will get a station every seven to 10 blocks, with a focus on transit nodes and commercial districts. The easternmost station will be just east of SE Cesar Chavez Boulevard at Taylor Street; the northernmost will be just south of N Killingsworth at Albina. Southeast Woodward will form most of the southeast boundary.

“There’s more stations that we want to put down,” Hoyt-McBeth said. “We would love to fill in, and I think over time we can expand.”

Scattered among the city’s 100 stations will be 18 “kiosks,” enhanced stations that let you buy a membership with a credit card. (You’ll also be able to do so anywhere using a mobile phone or the Internet.)

City expects “a lot of blowback” when stations appear in three weeks

The Biketown equipment has already begun arriving in city warehouses and the racks will appear on streets in the “beginning of July,” said Biketown general manager Dorothy Mitchell, a former city employee now running the system on behalf of operator Motivate.

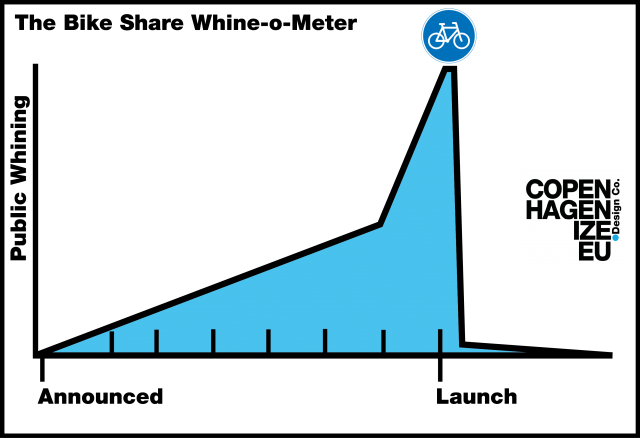

“We’re preparing ourselves based on what we’ve seen in other cities for a lot of blowback,” Hoyt-McBeth said. “It’s something new. People don’t know what it is.”

If that’s the case, Hoyt-McBeth argues it won’t be for lack of trying. He said the city based its station locations in part on 4,500 comments submitted online, at five open houses around the city this spring and at 40 stakeholder or community meetings over recent months.

Some stations will sit in street space currently used for auto parking. Hoyt-McBeth said the city’s parking operations team continues to scour every station area to find ways to create new parking spaces and reduce or even eliminate net parking loss.

“We’ve been able to find these obsolete no-parking zones, either from when a one-way street was two-way or there was a loading zone that somebody needed for a tenant that’s long gone,” he said. “We’re actually adding spaces back in as the system rolls out.”

Outreach to low-income Portlanders planned

Unlike private bicycle transportation, most modern bike sharing systems in the United States have struggled to attract users who are anything other than educated, white and relatively well-to-do. In Washington DC, for example, 25 percent of people who work in the city are African-American, but only 3 percent of Capital Bikeshare members are.

No one’s quite sure why this is true; there are probably multiple reasons.

Portland recently scored a grant to try to do better with Biketown.

The $75,000 grant from the Better Bike Share Partnership will fund a partnership with the Community Cycling Center, which will replicate its longstanding Earn a Bike Program for bike sharing by offering free classes to low-income Portlanders. If they finish, they’ll earn what Hoyt-McBeth said will be “near free” bike-share memberships.

“The CCC will be going to affordable housing units, knocking on doors, telling people about bike share,” he said. Or “a social worker will call and say, hey, so-and-so needs a bike. We’re going to kind of leverage those relationships that the CCC has.”

The city hopes it’ll help that it’s deliberately located many stations very close to publicly supported housing units.

Of the 13,000 such housing units in service area — which is 55 percent of the 23,600 citywide, the Mercury reported — Hoyt-McBeth said, 96 percent are within quarter-mile of a Biketown station and 64 percent are within 500 feet of a biketown station.

(Disclosure: my other job as a staff writer for PeopleForBikes includes editing the Better Bike Share Partnership’s website. I’m not involved in the grant process.)

System will offer goodies for ‘Founding members’

In addition to the free first month for the first 500 people to commit to the $12-a-month membership, the first 1,000 to sign up will be designated as “founding members” and receive a specially branded t-shirt and bike share access card that they’ll get to use permanently.

Because Portland’s pricing system is unique — a relatively high annualized rate with no month-to-month option, but billed using monthly payments that are smaller than the monthly rate anywhere in North America — Biketown will break new ground in bike share pricing. Mitchell, the general manager, said with an only slightly uneasy smile that she’ll be interested to see how fast the memberships sell.

Whatever happens, there’s no question that this’ll be a historic summer for bicycle transportation in Portland.

“This is a new public transit system,” Hoyt-McBeth said. “We have streetcar and aerial tram, and this is our third.”

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today.

The post Portland’s bike-sharing system just started selling memberships at $12 a month appeared first on BikePortland.org.

from BikePortland.org http://ift.tt/1tu4YIQ

No comments:

Post a Comment