“How can bicycle advocacy be more inclusive?” and “How can we make streets safer without causing gentrification?” were central questions that Portlanders asked at a standing room only event on Thursday night.

“Transportation safety [advocacy] is tied up in other ways we decide who’s important and who’s not important.”

— Dr. Adonia Lugo

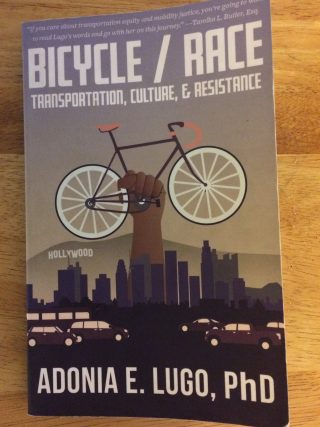

Adonia Lugo, a former bicycle activist with a PhD in anthropology, spoke at a packed event last night. Her recently published book, Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, and Resistance (2018, Microcosm Publishing), follows the trajectory of her cycling experience — from becoming a bike commuter in Portland, to her work establishing the CicLAvia open streets event in Los Angeles, to her struggle to integrate equity during her tenure at the League of American Bicyclists in Washington D.C.

Lugo’s book looks at the way a focus on the traditional bike advocacy focus on infrastructure doesn’t go far enough to dismantle the injustices on our streets. Lugo explained that when advocates talk about street safety as a goal it usually only focuses on vehicular interactions, but “mobility justice” looks at the broader picture of how our bodies are not just vulnerable to cars, but some bodies are also vulnerable to racial profiling, sexual harassment, or even not having the right documents.

After leaving Portland and returning to Southern California where she grew up, Lugo noticed the people who biked were people of color who didn’t seem to have access to a car. And something clicked: “People who were dealing with so many kinds of oppression and so many ways of being held back and denied access to the American dream also weren’t going to be safe as they travelled because they couldn’t afford to drive. For me, looking at transportation and transportation safety is tied up in other ways we decide who’s important and who’s not important.”

Lugo sees bicycling as a powerful decolonizing force, a way for people to feel powerful and mobile in their public spaces, and a way to reduce their tie into materialism and oil consumption. But a lot of advocates don’t see biking in the same way. “For a lot of people who get involved in bicycling or bike advocacy, their lives are maybe not that bad structurally, maybe they have access to economic security, maybe they grew up in a house their family owned, maybe they got to go to college, maybe they have a six-figure job and they love bicycling, and riding a bike is that one time of the day that they don’t feel safe or they feel like something is wrong with the system.”

The issue with infrastructure-only advocacy done mostly by people of privilege, Lugo says, is that when we define the problem of safety so narrowly, we often come up with a narrow set of solutions.

During her presentation, Lugo walked us through how the urban planning field is fraught with inequality. This field has decided to take examples of roads in Northern Europe that we like, and change roads in U.S. cities to be similar. In doing that, a whole industry was built that perpetuates the problems of who gets to decide which urban design projects are failures, and which ones are still worth pursuing. The planning process requires access and agreement to public officials and agencies, and planning and design firms who benefit from our public tax dollars. When those people get paid for months to manage those projects before community engagement even begins it reinforces the unequal power dynamic.

What would a better public engagement process look like? There is no easy checklist to follow and Lugo wouldn’t want to create one. Often well-meaning advocates push for projects on behalf of these communities, without people from the community itself defining the problem of what needs to be solved. Engagement needs to happen much earlier — before proposals have momentum behind them — to be authentic. Funding also needs to be more flexible to accommodate types of “human infrastructure” that the community needs; such as neighborhood bike shops and programming for residents. Lugo believe we need to invest in experimental processes for a different kind of community engagement.

Several people in the audience asked about the controversy around North Williams, and the current tension around the Lloyd to Woodlawn greenway project. There were no easy answers about what the path forward should be, but Lugo recommended some books that dive deeper into the topic of bike lanes and gentrification such as Bike Lanes are White Lanes (2016, University of Nebraska Press) by Melody Hoffman and Bicycle Justice and Urban Transformation: Biking for All? (2016, Routledge), which Lugo also co-authored.

For Lugo, the fight for transportation justice isn’t all about a war on cars. America’s history of segregation and racism should be the main story, not just a footnote.

— Catie Gould, @Citizen_Cate on Twitter

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

The post Urban anthropologist Adonia Lugo leads discussion on bike advocacy and race appeared first on BikePortland.org.

from BikePortland.org https://ift.tt/2zlS7gb

No comments:

Post a Comment